Early years

Mary Hockerday was born on 13 May 1842 at Pollard Street in Bethnal Green, the daughter

of Thomas Hockerday and Ann Maria Sutton. By 1848, she had three sisters and a brother,

another brother, Thomas Henry, having died in infancy. Hers was not an easy start

in life, although if one had asked her, she would probably have said that it was

no different to that of her friends and neighbours. Her mother died in 1848 when

she was only six years old, and was followed by a succession of step-mothers, the

first of which was Elizabeth Durham, a 38-year old widow who, by 1850 had already

buried three of her five children. Elizabeth herself did not survived much longer,

dying in January 1854 of consumption.

After Elizabeth’s death, Mary Ann found herself with a second step-mother, Elizabeth

Pratt (née Reader) whom her father married in May 1854. This arrangement did not

last long and by 1857, Mary Ann’s father had separated from Elizabeth to live with

Esther Bostock (née Steward). Esther was a widowed silk weaver from Spitalfields

who had five children from her marriage to George Bostock, ranging from six to 18

years of age. This meant that Thomas and Esther’s combined family numbered around

eleven children.

By the time of her father’s ‘marriage’, Mary Ann was working as a silk weaver. The

silk weaving industry had once flourished in Spitalfields and Bethnal Green, but

had been in terminal decline for some years and the silk weavers of Bethnal Green

were, for the most part, out of work. Those that did have employment, worked long

hours for low wages.

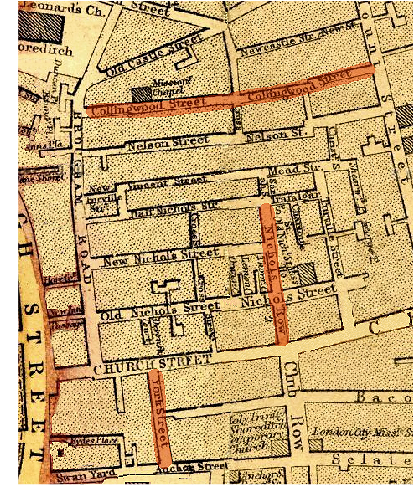

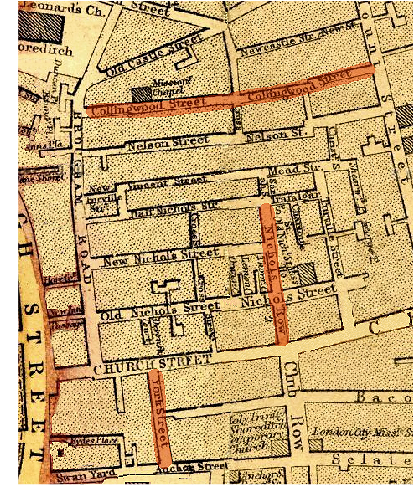

The Old Nichol

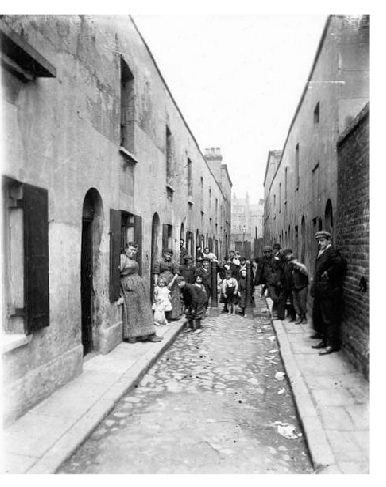

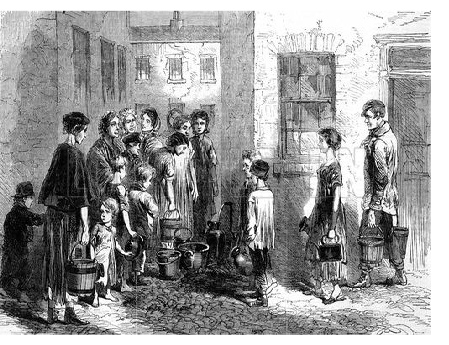

By August 1866, Mary Ann had left home and was living at 1 Nichols Row. It was one

of the streets that comprised the notorious area known as the Old Nichol. The area

was a dense network of about thirty streets, courts and alleys spread over fifteen

acres  filled with tenement buildings, some so close together that a man had to turn

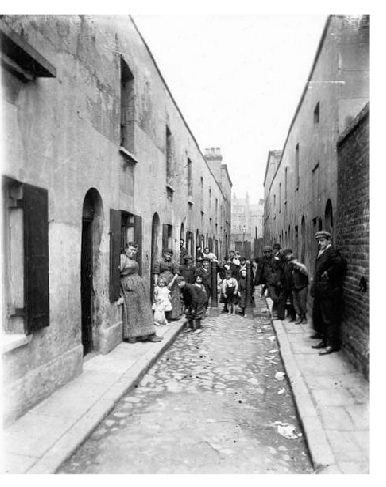

sideways to pass between them. The photograph on the left shows Little Collingwood

Street in about 1900. The buildings were badly built, and lack of proper foundations

and cheap building material meant that the damp soaked down from the rafters and

up from the ground to meet in the middle, causing the walls to bow and shed their

plaster. By the 1880s it was known as the worst slum in London. Over half the houses

in the Nichol consisted of one-room dwellings and a reporter for The Builder found

48 people in a six-roomed house. “To supply these with water, a stream runs for ten

or twelve minutes each day, except Sunday, from a small tap at the back of one of

the houses...”. This rabbit warren, barely fit for human habitation, was home to

over 5,700 people.

filled with tenement buildings, some so close together that a man had to turn

sideways to pass between them. The photograph on the left shows Little Collingwood

Street in about 1900. The buildings were badly built, and lack of proper foundations

and cheap building material meant that the damp soaked down from the rafters and

up from the ground to meet in the middle, causing the walls to bow and shed their

plaster. By the 1880s it was known as the worst slum in London. Over half the houses

in the Nichol consisted of one-room dwellings and a reporter for The Builder found

48 people in a six-roomed house. “To supply these with water, a stream runs for ten

or twelve minutes each day, except Sunday, from a small tap at the back of one of

the houses...”. This rabbit warren, barely fit for human habitation, was home to

over 5,700 people.

The conditions meant that inhabitants of the Nichol were almost twice as likely to

die than those in other areas of Bethnal Green; a shocking statistic given that mortality

rates in Bethnal Green were some of the highest in the capital. In an article of

1863, T he Illustrated London News summed up life there as "one painful and monotonous

round of vice, filth, and poverty, huddled in dark cellars, ruined garrets, bare

and blackened rooms, teeming with disease and death, and without the means, even

if there were the inclination, for the most ordinary observations of decency or cleanliness”.

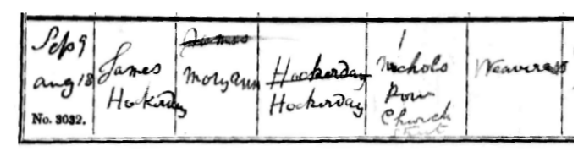

It was into this world that Mary Ann’s son was born on 18 August 1866. She named

him James, although whose child he was in unknown;

he Illustrated London News summed up life there as "one painful and monotonous

round of vice, filth, and poverty, huddled in dark cellars, ruined garrets, bare

and blackened rooms, teeming with disease and death, and without the means, even

if there were the inclination, for the most ordinary observations of decency or cleanliness”.

It was into this world that Mary Ann’s son was born on 18 August 1866. She named

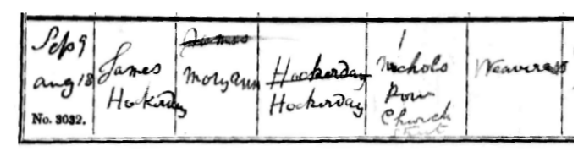

him James, although whose child he was in unknown;  when he was baptised on 9 September

1866 at the Church of St Matthias, Bethnal Green, no father’s name was entered into

the baptism register (shown below). Living in the Old Nichol, young James had a three

in four chance of surviving infancy. As for Mary Ann, her best chance was to find

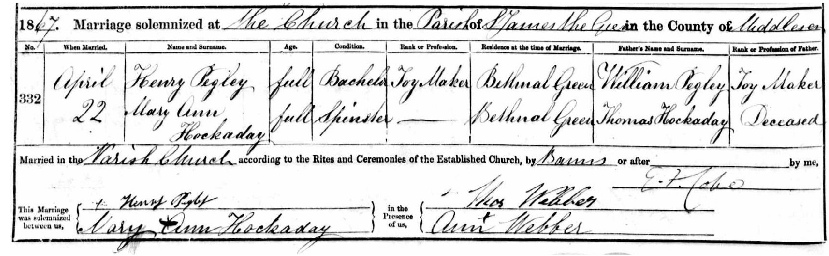

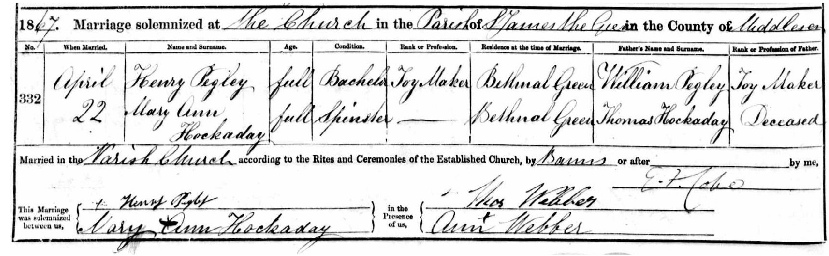

a husband, which she did. Henry Pegley (who may have been young James’ father) was

a toy maker from St Luke’s living in Bethnal Green. Mary Ann married him on 22 April

1867 at the Church of St James the Great, Bethnal Green. Like all couples who married

at the Church, the vicar did not charge for the service and, at the end of it, presented

them with a sixpence and a loaf of bread to help them start their married life. These

measures had been introduced in 1852 in an attempt to help couples who could not

otherwise afford to marry to keep faith with Christian teachings and, one assumes,

to prevent couples from ‘living in sin’. In many cases, including that of Mary Ann,

it failed to have the desired effect. Three years after Mary Ann’s wedding to Henry

Pegley, on 25 October 1870, Mary Ann gave birth to a son; the father was not Henry,

but James George Bostock.

when he was baptised on 9 September

1866 at the Church of St Matthias, Bethnal Green, no father’s name was entered into

the baptism register (shown below). Living in the Old Nichol, young James had a three

in four chance of surviving infancy. As for Mary Ann, her best chance was to find

a husband, which she did. Henry Pegley (who may have been young James’ father) was

a toy maker from St Luke’s living in Bethnal Green. Mary Ann married him on 22 April

1867 at the Church of St James the Great, Bethnal Green. Like all couples who married

at the Church, the vicar did not charge for the service and, at the end of it, presented

them with a sixpence and a loaf of bread to help them start their married life. These

measures had been introduced in 1852 in an attempt to help couples who could not

otherwise afford to marry to keep faith with Christian teachings and, one assumes,

to prevent couples from ‘living in sin’. In many cases, including that of Mary Ann,

it failed to have the desired effect. Three years after Mary Ann’s wedding to Henry

Pegley, on 25 October 1870, Mary Ann gave birth to a son; the father was not Henry,

but James George Bostock.

Family life

Mary Ann probably first met J ames George in the 1850s when she was about 15 years

old. He was two years younger than her and the son of Esther and George Bostock.

When the widowed Esther started living with Thomas Hockerday in about 1857, Mary

Ann and James George became, in practice if not law, step-brother and -sister, although

James George continued to live with his grandmother. Taking this into account, it

is difficult to understand why, if Mary Ann and James George had known one another

since their teens, Mary Ann had married Henry Pegley; one explanation is that Henry

was the father of Mary Ann’s child, James. It is also possible that Mary Ann was

pregnant with James George Bostock’s child when she left her husband, Henry, only

a few years after their marriage. It was a tangled web.

ames George in the 1850s when she was about 15 years

old. He was two years younger than her and the son of Esther and George Bostock.

When the widowed Esther started living with Thomas Hockerday in about 1857, Mary

Ann and James George became, in practice if not law, step-brother and -sister, although

James George continued to live with his grandmother. Taking this into account, it

is difficult to understand why, if Mary Ann and James George had known one another

since their teens, Mary Ann had married Henry Pegley; one explanation is that Henry

was the father of Mary Ann’s child, James. It is also possible that Mary Ann was

pregnant with James George Bostock’s child when she left her husband, Henry, only

a few years after their marriage. It was a tangled web.

In these early years of her relationship with James George Bostock, Mary Ann supplemented

the family’s income by silk weaving, although by this time, the industry was a shadow

of its former self and the majority of East End silk weavers were out of work or

had taken other employment. The centre of the silk weaving industry had been Spitalfields

and Bethnal Green and it was here that Mary Ann and her family lived until the early

1880s. During this period, Mary Ann gave birth to four more children: Albert (1872),

Esther Harriet (1877), Edwin Francis (1879) and Rosina (1880). In 1881 there was

a brief move to Cullum Street in West Ham. It was after returning from West Ham that

Mary Ann and James George finally married on 21 May 1883 at the Church of St Thomas.

The marriage was witnessed by James George’s sister, Ann Martha Hart (née Bostock).

No evidence has been discovered yet about this date. A logical conclusion would be

that Henry Pegley had died, leaving Mary Ann a widow and free to marry James George.

However, the only death certificates that have been found date from 1890 and 1892.

Interesting, there is a marriage entry for Henry Pegley (a toy maker and the son

of William Pegley, a toy maker) to a Caroline Diss in November 1870. On paper, the

evidence suggests that the two Henry Pegleys were one and the same; in the nineteenth

century, divorce was expensive and difficult and bigamy was not uncommon, but if

Henry (and later Mary Ann) were guilty, it was a brazen act, although perhaps if

both parties were in agreement, the chances of being caught and punished were slight.

Details about the twenty-five years from 1883 to 1908 are scant. In 1891, Mary Ann

and her family were living in Bethnal Green; unlike many families, they were renting

the whole house. Mary Ann was no longer working, her day filled with taking care

of the house and her family. On the night of the 1901 census, James George was in

hospital suffering with gout; Mary Ann’s whereabouts have not been traced but she

was not staying with any of her children.

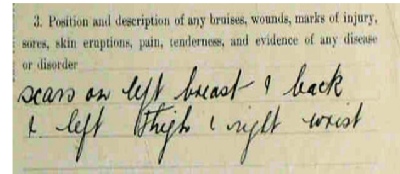

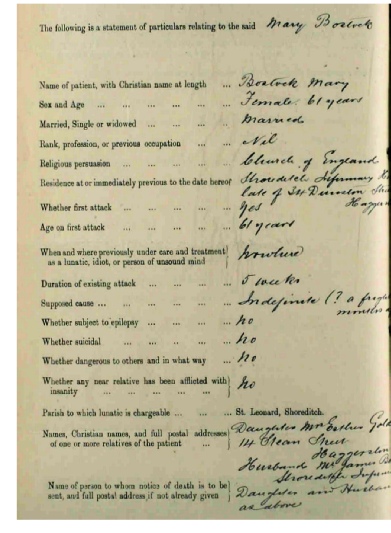

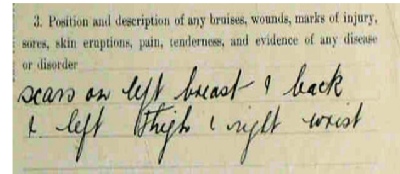

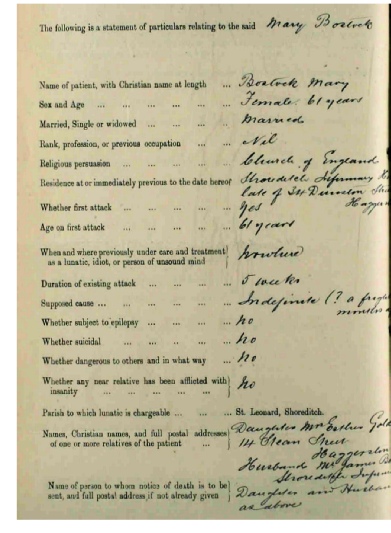

A turn for the worse

By the 1900s, James George was sixty years old and suffering with gout. He may have

found it difficult to work and finances were difficult. Mary Ann may have worked

in a tobacconist newsagents to help supplement the family income. In 1909, an event

occurred that was to have a profound effect on both Mary Ann and James George. On

6 August 1909, Mary Ann’s daughter, Esther, took her to Shoreditch Infirmary and

Workhouse where she was admitted as a ‘pauper lunatic’ and ‘a person requiring to

be dealt with in accordance with the provisions of the Lunacy Act’. A medical report

attests that she was ‘clean’ and her bodily condition ‘fair’, but she had ‘scars

on left breast and back and left thigh and right wrist’ (the image on the left shows

part of the report). James George was in Shoreditch Infirmary.

The events leading up to this incident are unclear. According to Mary Ann’s g randdaughter,

Irene, Mary Ann was twice robbed and badly beaten whilst working in the tobacconist

newsagents. The second time, in early July 1909, the family returned home to find

her weeping, with blood pouring from her head and tearing up papers and documents,

saying that if she burnt them “they can’t hurt me any more”. The 1871 census records

that a ‘Mary Ann Bostock’ ran a tobacconist at 2 Pritchard’s Place, an address associated

with the Bostock family since the 1860s; this was most probably James George’s aunt,

Mary Ann Bostock (née Welsford), but is is possible that by the 1900s, Mary Ann

(née Hockerday) was running the shop.

randdaughter,

Irene, Mary Ann was twice robbed and badly beaten whilst working in the tobacconist

newsagents. The second time, in early July 1909, the family returned home to find

her weeping, with blood pouring from her head and tearing up papers and documents,

saying that if she burnt them “they can’t hurt me any more”. The 1871 census records

that a ‘Mary Ann Bostock’ ran a tobacconist at 2 Pritchard’s Place, an address associated

with the Bostock family since the 1860s; this was most probably James George’s aunt,

Mary Ann Bostock (née Welsford), but is is possible that by the 1900s, Mary Ann

(née Hockerday) was running the shop.

During the time that Mary Ann was in Shoreditch Workhouse, she was examined and declared

to be a person of ‘unsound mind’. The doctor commented that ‘she is restless, her

memory is defective, she wanders about the ward, c annot give a relevant account of

her recent doings’, and again ‘she is quite lost, fancies she has been out this morning;

she cannot give a relevant account of her recent doings, her memory is very defective’.

On 4 September the doctor committed her to the care of Long Grove Asylum in Epsom,

Surrey as someone of ‘unsound mind’, although neither suicidal nor a danger to others.

The medical records give little clue as to the cause of her mental state: in the

medical report for Long Grove under supposed cause, the word ‘indefinite’ has been

written, although to one side and in brackets is written (? a fright... and then

a word which is indecipherable). If the story recounted to Irene is true, then it

would indicate that Mary Ann was suffering from post-traumatic stress.

annot give a relevant account of

her recent doings’, and again ‘she is quite lost, fancies she has been out this morning;

she cannot give a relevant account of her recent doings, her memory is very defective’.

On 4 September the doctor committed her to the care of Long Grove Asylum in Epsom,

Surrey as someone of ‘unsound mind’, although neither suicidal nor a danger to others.

The medical records give little clue as to the cause of her mental state: in the

medical report for Long Grove under supposed cause, the word ‘indefinite’ has been

written, although to one side and in brackets is written (? a fright... and then

a word which is indecipherable). If the story recounted to Irene is true, then it

would indicate that Mary Ann was suffering from post-traumatic stress.

Long Grove

Long Grove in Surrey was the third asylum constructed on the Horton Estate, and one

of a cluster of hospitals built to house the mentally ill. It opened in June 1907

and was designed to house 2,000 patients. As well as eight male and eight female

blocks, there was an administration block, recreation hall, male and female staff

blocks, kitchens, and main store. Gender specific workplaces such as laundry, workshops

and boiler house were also built on the side relating to their respective workforces.

There was a large semi-circular corridor with spur corridors making the entire main

complex easily accessible. The photograph on the left shows the main block in the

early twentieth century.

In the grounds were a water tower, parole and infirmary blocks, a chapel, senior

staff and official's housing and an isolation hospital. The hospital was regarded

as a showpiece and a report by the  Commissioners from March 1911 records that: ‘The

wards, dormitories and all parts of the building were in excellent order, and there

is a good supply of books, and of flowers, birds and objects of various kinds to

brighten the rooms and interest their inmates’. In addition, the grounds were exceptionally

well maintained and included a collection of rare trees, and the medical staff were

excellent.

Commissioners from March 1911 records that: ‘The

wards, dormitories and all parts of the building were in excellent order, and there

is a good supply of books, and of flowers, birds and objects of various kinds to

brighten the rooms and interest their inmates’. In addition, the grounds were exceptionally

well maintained and included a collection of rare trees, and the medical staff were

excellent.

Based on this report, life was probably quite pleasant for Mary Ann, but a far cry

from the hustle and bustle of her life in the east end of London. It is difficult

to know how much she was aware of her surroundings, or whether her condition worsened.

Whatever the case, Mary Ann was not at Long Grove for long. She died two years after

being admitted on 5 November 1911. The cause of death was given as a ‘fatty degeneration

of the heart’ and ‘arteriosclerosis (which is a hardening of the arteries); as the

main causes are smoking, obesity, diet and high blood pressure, no doubt most of

the damage had been done well before she entered Long Grove.

filled with tenement buildings, some so close together that a man had to turn

sideways to pass between them. The photograph on the left shows Little Collingwood

Street in about 1900. The buildings were badly built, and lack of proper foundations

and cheap building material meant that the damp soaked down from the rafters and

up from the ground to meet in the middle, causing the walls to bow and shed their

plaster. By the 1880s it was known as the worst slum in London. Over half the houses

in the Nichol consisted of one-

filled with tenement buildings, some so close together that a man had to turn

sideways to pass between them. The photograph on the left shows Little Collingwood

Street in about 1900. The buildings were badly built, and lack of proper foundations

and cheap building material meant that the damp soaked down from the rafters and

up from the ground to meet in the middle, causing the walls to bow and shed their

plaster. By the 1880s it was known as the worst slum in London. Over half the houses

in the Nichol consisted of one- he Illustrated London News summed up life there as "one painful and monotonous

round of vice, filth, and poverty, huddled in dark cellars, ruined garrets, bare

and blackened rooms, teeming with disease and death, and without the means, even

if there were the inclination, for the most ordinary observations of decency or cleanliness”.

It was into this world that Mary Ann’s son was born on 18 August 1866. She named

him James, although whose child he was in unknown;

he Illustrated London News summed up life there as "one painful and monotonous

round of vice, filth, and poverty, huddled in dark cellars, ruined garrets, bare

and blackened rooms, teeming with disease and death, and without the means, even

if there were the inclination, for the most ordinary observations of decency or cleanliness”.

It was into this world that Mary Ann’s son was born on 18 August 1866. She named

him James, although whose child he was in unknown;  when he was baptised on 9 September

1866 at the Church of St Matthias, Bethnal Green, no father’s name was entered into

the baptism register (shown below). Living in the Old Nichol, young James had a three

in four chance of surviving infancy. As for Mary Ann, her best chance was to find

a husband, which she did. Henry Pegley (who may have been young James’ father) was

a toy maker from St Luke’s living in Bethnal Green. Mary Ann married him on 22 April

1867 at the Church of St James the Great, Bethnal Green. Like all couples who married

at the Church, the vicar did not charge for the service and, at the end of it, presented

them with a sixpence and a loaf of bread to help them start their married life. These

measures had been introduced in 1852 in an attempt to help couples who could not

otherwise afford to marry to keep faith with Christian teachings and, one assumes,

to prevent couples from ‘living in sin’. In many cases, including that of Mary Ann,

it failed to have the desired effect. Three years after Mary Ann’s wedding to Henry

Pegley, on 25 October 1870, Mary Ann gave birth to a son; the father was not Henry,

but James George Bostock.

when he was baptised on 9 September

1866 at the Church of St Matthias, Bethnal Green, no father’s name was entered into

the baptism register (shown below). Living in the Old Nichol, young James had a three

in four chance of surviving infancy. As for Mary Ann, her best chance was to find

a husband, which she did. Henry Pegley (who may have been young James’ father) was

a toy maker from St Luke’s living in Bethnal Green. Mary Ann married him on 22 April

1867 at the Church of St James the Great, Bethnal Green. Like all couples who married

at the Church, the vicar did not charge for the service and, at the end of it, presented

them with a sixpence and a loaf of bread to help them start their married life. These

measures had been introduced in 1852 in an attempt to help couples who could not

otherwise afford to marry to keep faith with Christian teachings and, one assumes,

to prevent couples from ‘living in sin’. In many cases, including that of Mary Ann,

it failed to have the desired effect. Three years after Mary Ann’s wedding to Henry

Pegley, on 25 October 1870, Mary Ann gave birth to a son; the father was not Henry,

but James George Bostock.

ames George in the 1850s when she was about 15 years

old. He was two years younger than her and the son of Esther and George Bostock.

When the widowed Esther started living with Thomas Hockerday in about 1857, Mary

Ann and James George became, in practice if not law, step-

ames George in the 1850s when she was about 15 years

old. He was two years younger than her and the son of Esther and George Bostock.

When the widowed Esther started living with Thomas Hockerday in about 1857, Mary

Ann and James George became, in practice if not law, step- randdaughter,

Irene, Mary Ann was twice robbed and badly beaten whilst working in the tobacconist

newsagents. The second time, in early July 1909, the family returned home to find

her weeping, with blood pouring from her head and tearing up papers and documents,

saying that if she burnt them “they can’t hurt me any more”. The 1871 census records

that a ‘Mary Ann Bostock’ ran a tobacconist at 2 Pritchard’s Place, an address associated

with the Bostock family since the 1860s; this was most probably James George’s aunt,

Mary Ann Bostock (née Welsford), but is is possible that by the 1900s, Mary Ann

(née Hockerday) was running the shop.

randdaughter,

Irene, Mary Ann was twice robbed and badly beaten whilst working in the tobacconist

newsagents. The second time, in early July 1909, the family returned home to find

her weeping, with blood pouring from her head and tearing up papers and documents,

saying that if she burnt them “they can’t hurt me any more”. The 1871 census records

that a ‘Mary Ann Bostock’ ran a tobacconist at 2 Pritchard’s Place, an address associated

with the Bostock family since the 1860s; this was most probably James George’s aunt,

Mary Ann Bostock (née Welsford), but is is possible that by the 1900s, Mary Ann

(née Hockerday) was running the shop.  annot give a relevant account of

her recent doings’, and again ‘she is quite lost, fancies she has been out this morning;

she cannot give a relevant account of her recent doings, her memory is very defective’.

On 4 September the doctor committed her to the care of Long Grove Asylum in Epsom,

Surrey as someone of ‘unsound mind’, although neither suicidal nor a danger to others.

The medical records give little clue as to the cause of her mental state: in the

medical report for Long Grove under supposed cause, the word ‘indefinite’ has been

written, although to one side and in brackets is written (? a fright... and then

a word which is indecipherable). If the story recounted to Irene is true, then it

would indicate that Mary Ann was suffering from post-

annot give a relevant account of

her recent doings’, and again ‘she is quite lost, fancies she has been out this morning;

she cannot give a relevant account of her recent doings, her memory is very defective’.

On 4 September the doctor committed her to the care of Long Grove Asylum in Epsom,

Surrey as someone of ‘unsound mind’, although neither suicidal nor a danger to others.

The medical records give little clue as to the cause of her mental state: in the

medical report for Long Grove under supposed cause, the word ‘indefinite’ has been

written, although to one side and in brackets is written (? a fright... and then

a word which is indecipherable). If the story recounted to Irene is true, then it

would indicate that Mary Ann was suffering from post- Commissioners from March 1911 records that: ‘The

wards, dormitories and all parts of the building were in excellent order, and there

is a good supply of books, and of flowers, birds and objects of various kinds to

brighten the rooms and interest their inmates’. In addition, the grounds were exceptionally

well maintained and included a collection of rare trees, and the medical staff were

excellent.

Commissioners from March 1911 records that: ‘The

wards, dormitories and all parts of the building were in excellent order, and there

is a good supply of books, and of flowers, birds and objects of various kinds to

brighten the rooms and interest their inmates’. In addition, the grounds were exceptionally

well maintained and included a collection of rare trees, and the medical staff were

excellent.